What you need to know about child sexual abuse

Learn more about child sexual abuse based on key research and statistics: what it is, who harms children, where it takes place, the impact on children and what we all can do in response.

Jump ahead to any topic you like

Remember, it is never a child’s responsibility to prevent abuse, protect themselves or make the abuse stop. But by better understanding child sexual abuse, having conversations and highlighting concerns, we can all play a role in better protecting children.

Scroll to the bottom of this overview to explore further research and practical resources for professionals to help identify and respond to child sexual abuse. Download the Welsh translation of this resource here.

If you are worried that a child may have been or is being sexually abused, or you are concerned about someone’s behaviour, it’s important to take action. Visit our Get Support page for contact details of organisations who can help

1. Child sexual abuse is more common than most people think, and far more children are sexually abused than are ever identified or responded to.

2. Children can be sexually abused in many different ways, by different people and in different places and situations, including online.

Child sexual abuse is defined by UK Government as:

forcing or enticing a child or young person to take part in sexual activities, not necessarily involving a high level of violence, whether or not the child is aware of what is happening. The activities may involve physical contact, including assault by penetration (for example, rape or oral sex) or non-penetrative acts, such as masturbation, kissing, rubbing, and touching outside of clothing. They may also include non-contact activities, such as involving children in looking at, or in the production of, sexual images, watching sexual activities, encouraging children to behave in sexually inappropriate ways, or grooming a child in preparation for abuse.

- Children can be sexually abused in family settings and outside the home, and they can be abused by adults, young people and children.

- Almost half of all child sexual abuse offences reported to the police in England and Wales in 2021/22 took place in the family environment. That means the abuse was by parents, siblings, grandparents or anyone considered ‘one of the family’.

- Another form of child sexual abuse is child sexual exploitation, where an individual or a group uses their power to force, manipulate or persuade a child or young person to take part in sexual activities.

- Children can be sexually exploited through direct physical contact, through technology, or both at the same time. While children and young people may appear to cooperate with those exploiting them, professionals working with children must remember this cannot be taken as consent. Instead, these children are likely to be subject to many forms of grooming, coercion and control.

- It is common for those who sexually abuse children to use ‘grooming’ techniques to gain compliance and ensure a child’s silence. They may use threats and force, but often use rewards, favouritism and alienation from friends and family, or take advantage of the normalisation of potentially abusive activities. Similar techniques may be used on families and colleagues to secure access to victims and prevent detection. This can take place online and in person.

- A significant proportion of child sexual abuse is carried out by other children and young people, and sexual harassment and abuse between students in school is widespread and can become ‘normalised’.

- ‘Harmful sexual behaviour’ is a term used to describe a range of behaviours by children and young people under 18, from those considered ‘inappropriate’ at a particular developmental stage to ‘problematic’, ‘abusive’ and ‘violent’ behaviours.

- After sexual abuse by a parent, harmful sexual behaviour by siblings is the second most common form of child sexual abuse within the family environment reported to police.

- One in 10 victims and survivors of child sexual abuse involving physical contact were abused by a person in a position of trust or authority. This includes people working in institutional settings like schools, hospitals and residential care, or in settings such as sports clubs or religious groups.

- Today, digital technologies feature in almost all types of child sexual abuse. This can include through sexual conversations with children online, persuading children to pose naked or perform sexual acts on video or via webcam, taking images or videos of sexual abuse, viewing and/or sharing images, or communicating with a child online with the intent of abusing them in person later.

- In a US survey, one in six young adults (aged 18–28) reported being sexually abused before the age of 18 – by intimate partners, friends, relatives or acquaintances – either online or through phone messages. This included being forced or threatened to provide intimate images or videos, and unwanted sexual talk or questions.

- More recently, artificial intelligence tools are being used to produce convincing, lifelike images of almost anything. These tools are increasingly being used for harmful purposes, including the creation of child sexual abuse images. It’s important to remember that it is illegal to create, view or share any images of child sexual abuse, including when they are artificially created.

3. Children are most often sexually abused by someone they know and trust. People who abuse come from all walks of life, are not readily distinguishable, and sometimes are still children themselves.

Over one-third of victims and survivors of child sexual abuse involving physical contact said they were abused by a friend or acquaintance of theirs or their family’s. More than one in 10 said they were abused by their father/stepfather in childhood. Almost a quarter said their sexual abuse involved a family member other than a parental figure.

Some children are abused by other children and young people. In one US survey, roughly one-third of victims/survivors of child sexual abuse in online contexts said they had been abused by other under-18s, just over a third by people aged 18–25, and only one in seven by older adults.

Where ethnicity was recorded, 88% of the people prosecuted for child sexual abuse offences in 2022 were White.

Child sexual abuse is a gendered issue. In 2022/23, almost 99% of individuals convicted of child sexual abuse were men. However, both men and women can and do sexually abuse children.

There are a range of complex pathways into sexual offending and it is not possible to distinguish those who sexually offend from those who don’t. People who sexually abuse children come from all walks of life.

4. Any child, of any age, may be sexually abused. It is just as common as other forms of childhood abuse – though some children are more likely to be abused than others.

- Children who have been neglected are five times as likely as other children to have also experienced child sexual abuse.

- People who lived in a care home as children were nearly four times as likely as to have experienced child sexual abuse.

- Those who lived in a household with someone with a long-term mental health problem or disability, or with someone misusing alcohol or drugs, were three times as likely to have been sexually abused as those who did not.

More than half of adults who described being sexually abused in childhood said they had also experienced other forms of childhood abuse. One in six said they had been physically, emotionally and sexually abused, and had witnessed domestic violence, as children.

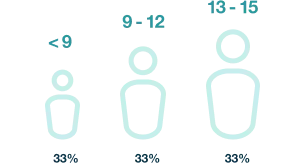

Child sexual abuse has been found to be just as common as childhood physical abuse. Among adults who described being sexually abused in childhood, one-third said they were first abused before the age of nine, another third said the abuse started between ages nine and 12 and the remaining third said it started between the ages of 13 and 15.

Age at which adults said they were first abused as a child

- Disabled children are at a higher risk of sexual abuse than non-disabled children. They are more dependent on caregivers, experience greater barriers in communication, and are less likely to have their abuse identified, particularly in a family setting.

- Child sexual abuse occurs across all ethnicities, but victims and survivors from minority ethnic backgrounds often face additional barriers in telling anyone and in accessing and receiving support.

5. Most children do not tell anyone about sexual abuse at the time. All adults need to be alert and responsive to concerns. Anyone working with children must be confident in spotting the signs and indicators of child sexual abuse.

- The majority of victims and survivors of child sexual abuse said they never told anyone about the abuse at the time. In one research survey, one in five had never told anyone before.

- Children are more likely to speak to friends or family than a professional, and friends are typically the first to recognise when young people are struggling.

- There are lots of barriers preventing children from talking about sexual abuse, and many will feel unable to tell professionals directly what is happening – or recognise that they are being, or have been, abused. Many victims and survivors find that sharing their experiences, or understanding them fully, is only possible in adulthood.

- All professionals need to be confident they have the knowledge and skills to recognise when children might be showing them that something is wrong.

- Children may display different signs of having been abused, including emotional, behavioural and/or physical signs. Be alert too for indicators of harm in the people around the child, or vulnerabilities in the family or environment around them.

- It is important to understand these signs, explore concerns, and build a picture of what they may be showing. The CSA Centre’s Signs and Indicators Template provides a common language for professionals to discuss, record and share such concerns that a child is being, or has been, sexually abused, and to act on them.

6. You don’t have to be an expert in child sexual abuse to help a child if you think they are at risk, or to act when you have concerns. Safeguarding children must be everyone’s responsibility.

If you have any concerns that a child may have been sexually abused in any way, or is at risk of sexual abuse, the appropriate response in most cases is to contact children’s social care and/or the police. If you want to talk to someone about your concerns, you can contact the NSPCC Helpline on 0808 800 5000 and their specialist team will listen, advise and take any action needed. You can also find local support by searching our Support Services Directory.

- It is not a child’s responsibility to prevent abuse, protect themselves or make the abuse stop.

- No single agency can do this alone. All professionals need to focus on meeting the child’s needs, taking note of how they are feeling and what they hope will happen. The CSA Centre created an online interactive resource, the Response Pathway, which sets out how to respond to concerns of child sexual abuse at key points: from first concerns and initial safeguarding actions through to child protection and criminal justice responses. By working together, services really can help better protect and support children and their families.

- If you have concerns about a child, it’s important to think first ‘what if I’m right?’ rather than ‘what if I’m wrong?’ It is natural to hope your concerns don’t mean that a child is being sexually abused, and to worry about getting it wrong. But whatever your relationship to the child, it is important to focus on considering ‘What if I am right?’ The experiences of victims of child sexual abuse shows that, too often, adults don’t act on this question and children are left to be abused in silence.

- If you are a professional who already works with children, or vulnerable adults, it’s important to remember you already have the skills needed to have sensitive, potentially uncomfortable conversations with children and families. You don’t need to be an ‘expert’ or have specialist skills.

- Children need you to use the skills you already have, to lean into your concerns and to explore all possibilities of what might be happening to a child, and what you can do to support them and protect them from sexual abuse.

7. Sexual abuse thrives in secrecy and silence. Society needs to confront the reality that this abuse does take place, and anyone working with children needs to feel confident in how to speak to children about it

- As a society, we need to talk openly about child sexual abuse: at home, at work, among friends, family and in our neighbourhoods.

- Although children and young people are more likely to tell friends or family than someone in a professional role, everyone working with children needs to be prepared to listen and respond sensitively, so that children feel safe to tell them if they are being sexually abused or are at risk.

- Children may not tell anyone that they have been abused. This could be because they are being threatened or manipulated, or because they fear the consequences of telling someone about the abuse.

- Children need help to tell. It should be a two-way interactive process that happens over time, between the child and adults around them. How adults respond to the signs of sexual abuse is pivotal in enabling a child to feel able to confide in them and express themselves further. Professionals working with children need to create a supportive environment where children can talk about their experiences and have an expectation of help.

- Children value support from professionals who are trustworthy, authentic, optimistic and encouraging; show care and compassion; facilitate choice, control and safety; and provide advocacy.

- It is important to remember that victims and survivors of child sexual abuse say they want adults to ask as early as possible, and to ask again, if they have concerns. In fact, being asked a second or third time gave them confidence that their experiences mattered, and reassured them that they would be listened to.

- The CSA Centre’s Communicating with Children Guide brings together research, practice guidance, and expert input – including from victims and survivors – to help give professionals the knowledge and confidence to build trust, start conversations, and act.

8. The experience and impacts of sexual abuse are different for every child

- Victims and survivors of child sexual abuse can be affected in a range of ways, but the impacts of abuse vary in their nature and extent. While the impact can be significant and life-long, people can, and do recover from sexual abuse and professionals can make a real difference, both at the time and in later life.

- No two people are affected in the same way, but impacts can include:

- Challenges with mental health and wellbeing, through anxiety disorders, depression, eating disorders and disturbances, sleep disruption and insomnia, and longer-term clinical psychiatric diagnoses such as post-traumatic stress disorder or personality disorders.

- Physical health changes across general health, gastrointestinal health, gynaecological or reproductive health, pain, weight, and general wellbeing. Physical impacts can often be linked to the victim or survivor’s mental health difficulties.

- Sexual functioning, and relationships in both adolescence and adulthood, may also be affected. Some adult victims and survivors may show protective parenting, but others may have difficulty creating and maintaining boundaries.

- The impacts of child sexual abuse can be influenced by different factors. This might include the age when a child’s abuse started, how long it lasted, their relationship with the person that abused them, other childhood experiences, and attachment to parents/carers. Whether children told someone about the abuse at the time, and what happened when they did, may also be important.

9. Parents and carers can, especially with help from professionals, play a key role in supporting their child to minimise the impacts of child sexual abuse and live a happy, healthy future.

10. People can and do recover from child sexual abuse. Even small actions can make a big difference.

- With the right support, children and families can and do recover.

- If you are a professional working with a child who you think may have been sexually abused, a compassionate and consistent response – recognising and responding to signs of the abuse, providing space for the child to tell, and accepting what they say when they do tell – can help limit the impacts of abuse.

- Intervening early when there are concerns of child sexual abuse can reduce stress and anxiety for victims and survivors: for professionals it’s important to provide information about what to expect, secure timely care, respect victims’ and survivors’ wishes and preferences, create a child-friendly environment, and provide a non-judgemental, validating response.

- Think about how you can provide hope. Children, young people and adults who have experienced sexual abuse report that they want professionals to have hope.

- When working with any child who has been sexually abused, it’s important to understand what has happened to the entire family to notice and challenge your own responses and maintain hope that the family can move forward. By doing so, you lay the groundwork to face what may initially seem like overwhelming challenges.

- Remember, sexual abuse thrives in secrecy. The more we talk about it, the more likely we are to notice signs of concern, take action to prevent abuse, to protect children when there are concerns and give them the support that they need.

Helpful resources

Key messages from research

Want to find more information? The ‘Key messages from research’ series provides succinct, easy-read summaries of the latest research in child sexual abuse to support confident, evidence-informed practice.

Signs and indicators template

The Signs and indicators template is designed to provide a common language among professionals to discuss, record and share concerns that a child is being, or has been, sexually abused.

Communicating with children guide

The Communicating with children guide helps give all professionals – not just those in specific safeguarding roles – knowledge and confidence to talk to children about sexual abuse.

eLearning

Want to improve your understanding of one of the most common contexts of child sexual abuse? Try our free course for all professionals working with children on Identifying and responding to intra-familial child sexual abuse