A question I often encounter is “How common is child sexual abuse?” It is a simple question which is difficult to answer. Difficult because abuse can take different forms, can be hidden, occurs in diverse contexts, and understanding of it can be impacted by different legal and policy frameworks.

Still, the simple question is extremely important. It reflects a strong need, particularly amongst practitioners and professionals who want to frame abuse within their everyday practice and the work of the organisations and systems around them. Is abuse more widespread than we think? Is there a number to attach to it? What does this mean for how I work in this organisation or with others?

My colleagues here at the Centre recently released an early report on their scoping work investigating the scale and nature of child sexual abuse and exploitation in England and Wales.

Their report highlighted the difficulties answering a simple question, as well as serious deficits in available data, particularly limitations in organisational recording. These deficits make it hard to talk with exact certainty about scale, but from current available evidence, they start with a suggested figure of at least 15% of girls and 5% of boys by age 16 in England and Wales. They point out the possibility of much higher figures, particularly in evidence from international studies. Data specifically on child sexual exploitation shows large growth in reporting over recent years and a significant issue across locations in England and Wales.

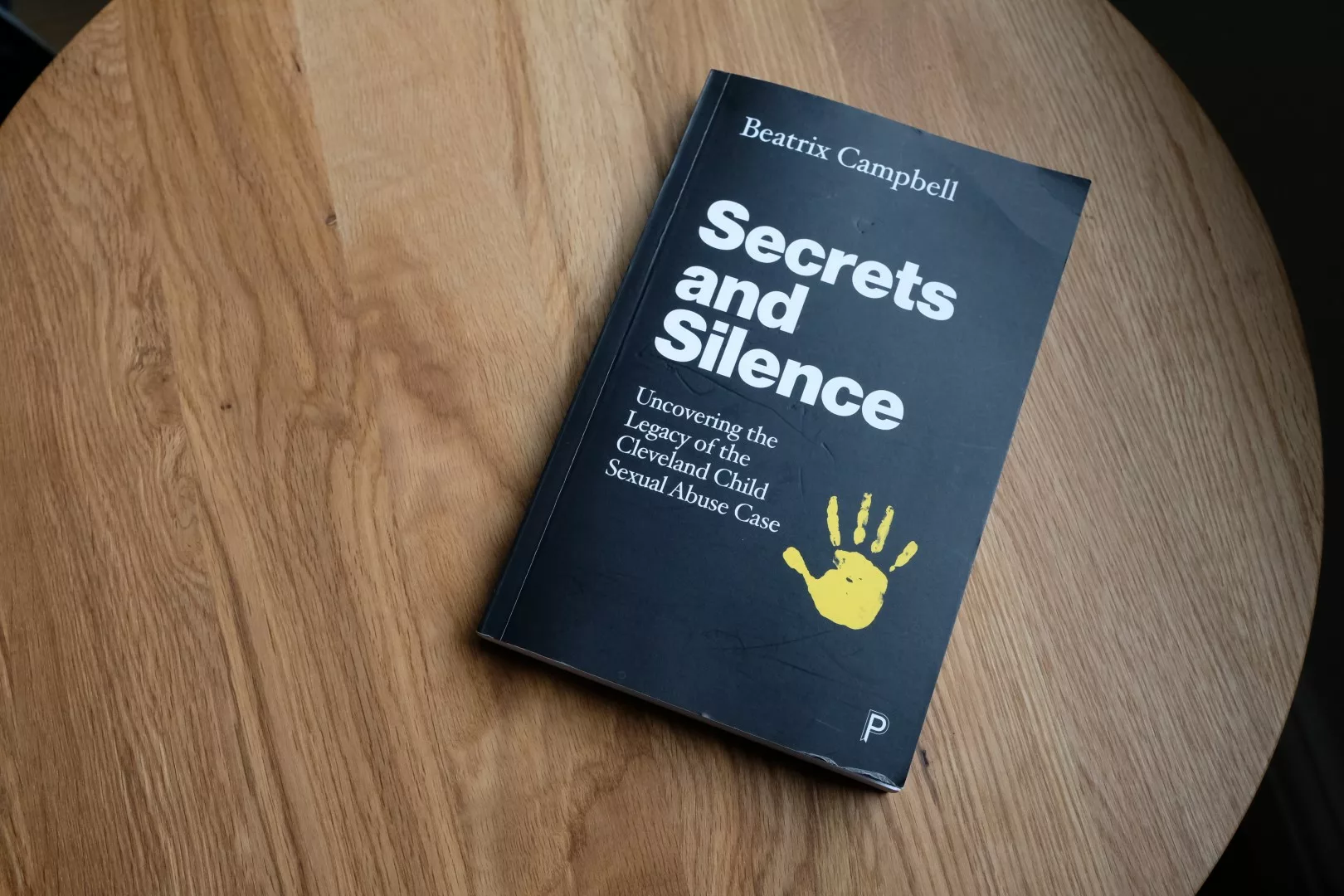

They also noted how child sexual abuse is often not recorded until much later in life, reinforcing the likelihood of a silent prevalence of abuse. Previous research from the NSPCC suggests that the idea of ‘disclosure’ later in life can obscure how some children may in fact ‘tell’ others about abuse earlier but be less well heard when they do so. This possibility is a problem for interventions oriented to ‘disclosure’, and reinforces the need for developing trusted relationships over time.

So, what does this mean for practice?

It is likely that workers in front-line areas of policing, education, health and children’s social care services are dealing much more often than is realised with children (and adults) who have experienced some kind of child sexual abuse. Just because workers aren’t encountering disclosures on a regular basis, doesn’t mean that they aren’t talking to, teaching or treating persons with experiences of abuse. Inquiries in Australia, the UK, and most recently in Germany have recognised the broad reach of abuse into diverse institutions and social contexts.

This means that practice education and professional development around child sexual abuse should be a priority. Those working in roles which help or exert authority over children or adults should have a good understanding of the complex and variable impacts of child sexual abuse. This should include a practical focus on how service relationships can exacerbate or lessen trauma, and how they can reiterate past powerful relationships.

Currently, we are a long way from this. Even key professionals who work with vulnerable children, such as social workers, qualify with limited knowledge and confidence around child sexual abuse and exploitation. There are assumptions that workers can easily build on a generic skills base after University but the reality is less clear.

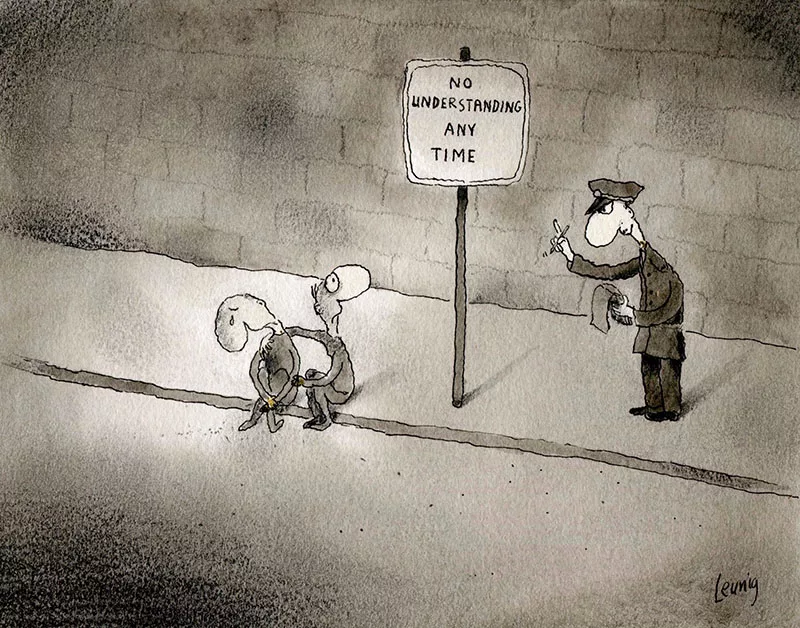

Many of those working at the frontline are new or recent graduates, whose expertise needs to develop through involvement in a cycle of growth with guidance from more expert colleagues. This can be challenging, particularly in environments with high turnover, geared to efficiency-talk and managing high volumes of contacts. Workers can become stuck in quick assessment-oriented interventions and pressures to work more distantly and defensively.

Credit: Michael Leunig

Contrast this with the needs of a child who has experienced sexual abuse – to be respected, heard and responded to on their own terms in their own time. The fundamental question for those involved in practice is how to engage authentically with a person and at the same time engage a complicated system to respond to their needs?

At the Centre, we are looking at how practitioners and systems can be better supported to understand and relate to the needs of children and adults impacted by or at risk of abuse. Two releases from the Centre highlight the issue of practice within systems with particular reference to child sexual exploitation.

First, the Centre’s upcoming report on child sexual exploitation risk assessment tools and checklists highlights the use (and challenges) of tools when applied to young people. The report suggests that an understandable organisational drive for better accountability has created a level of confusion for practice. Focus on young people as ‘risky’ can also lead to blaming of victims. The report, due for release in October, will provide advice on elements for more robust assessment, including contextual factors, and formats which encourage more open dialogue in multi-agency settings.

Second, the Centre’s report about supporting parents of sexually exploited young people focuses on an often missing link for practitioners and organisations. This report provides a framework for a more inclusive approach to parents, and encourages those working with individual young persons to consider how interventions and assessments can be enriched by a more family-based approach where safe and appropriate.

The Centre will be involved in consultations around these and other pieces of work in the coming months, to test findings with practitioners and organisational leaders in everyday practice. We are also consulting with people who have experienced practice from the other side, whose lived experience can better inform our advice. Apart from this consultation process, the Centre has just launched a practice scholarship programme to encourage professionals in a variety of fields related to child sexual abuse and exploitation to develop their expertise further.

If you have an interest in learning more about the Centre’s work, we would love to hear from you. More information about the Centre’s practice scholarship programme.